A breath of fresh air

In this article, George Schuetz, director of precision gauges at Mahr, discusses the virtues of air gauging against more traditional mechanical gauges.

Air gauges are often simpler and cheaper to engineer than mechanical gauges. They do not require linkages to transfer mechanical motion, so the ‘contacts’ (jets) can be spaced closely and at virtually any angle. This allows air gauges to handle tasks that would be difficult or extremely expensive with mechanical gauging.

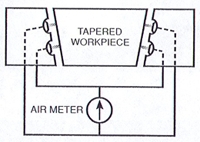

Gauging the straightness and/or taper of a bore is a basic application that benefits from close jet spacing (see Figure 1). All it takes is a single tool with jets at opposite sides of the gauge’s diaphragm. The gauge registers only the difference in pressure between the two sets of jets, directly indicating the amount of taper.

The concept can be applied to a fixture gauge to measure several diameters and tapers in a single operation. This fixture would be much simpler than a comparable gauge equipped with mechanical indicators, each one fitted, for example, with a motion transfer linkage and retracting mechanism. In addition, the air gauge could have an electrical interface to signal in- or out of tolerance conditions with lights – much quicker to read than dial indicators. Their flexibility is a key advantage.

Note the basic principle: air circuits operating on one side of a diaphragm measure dimensions; circuits on opposing sides measure relational measurements or differences between features. The beauty of the concept is that you can choose to ignore dimensions while seeing only relational measurements, and vice versa. Users never have to add, subtract or otherwise manipulate gauge data. Direct reading is all that is required.

Consider, for example, the fixture gate, which allows the shaft to rotate. Two jets on opposing sides of the journal, acting on the same side of the diaphragm, will accurately measure the diameter of the journal, even if it is eccentric to the shaft. As the shaft rotates, the air pressure increases at one jet, but decreases at the other. Total pressure against that side of the diaphragm remains constant, so a diameter is easily obtained.

If the two circuits operate on opposite sides of the diaphragm (see Figure 2), the gauge reflects not the total pressure of the circuits, but the difference between them. Higher pressure on one side or the other therefore, indicates the journal’s displacement from the shaft centreline.

Naturally, the user can position the jets and circuits to measure both features at once, and add another set to check for taper. Could you design a mechanical gate to accomplish all this at once? Perhaps, but at the cost of mechanical complexity.

The same principles apply to gauges designed to measure the squareness of a bore, the included angle of a tapered hole, or the parallelism (bend and twist) and distance between centres of two bores (such as, a connecting rod’s crank and pin bores). Bore gauges with the proper arrangement of jets can turn checking barrel shape, bell mouth, egg-shape, taper and curvature into quick, single step operations.

Contact-type air probes, which use air to measure the movement of a precision spindle, provide the major benefits of air gauging (high resolution and magnification) where the use of open-air jets is impracticable for use in measuring.

Open jets cannot measure against a point or a very narrow edge. The narrowest jet orifices are 0.025 inch, and these require a somewhat broader workpiece surface to generate the necessary air ‘curtain’ to read accurately. Contact-type air probes, however, can gauge with point or edge contact. Rough surfaces (above 50µin Ra) will baffle an open jet, but present no problems to a contact probe. And where open jets are limited in range to 0.003” to 0.006” measuring range, contact probes can go out to 0.03” (at some loss in sensitivity, however). Contact probes are often mounted in surface plates to measure flatness. Depth measurement of blind holes is another common use for long-range probes.

Come up for air

You need not be a gauge engineer to appreciate the flexibility of air gauging, or to understand how it can simplify gauging tasks. Just remember that virtually all kinds of measurements – both dimensional and relational – can be performed with air, and that the more complex the task, the more air recommends itself.

It is perfectly natural that machinists should have an affinity for mechanical gauges. To a machinist, the working of a mechanical gauge is both straightforward and traditional. Air gauges, on the other hand, rely on the action of a fluid material, the dynamics of which are more difficult to grasp. However, air gauging has many advantages over mechanical gauges and seriously considered as an option for many applications.

Air gauges are capable of measuring to tighter tolerances than mechanical gauges. The decision break point generally falls around 0.0005”; if your tolerances are tighter than that, air gauging provides the required resolution. At their best, mechanical gauges are capable of measuring down to 50 millionths of an inch, but that requires extreme care. Air gauges handle 50 millionths with ease, and some will measure to a resolution of five millionths.

Nevertheless, even if tolerances are around 0.0001” and mechanical gauging would suffice, air still provides several advantages.

The high-pressure jet of air automatically cleans the surface of the workpiece of most coolants, chips, and grit, aiding in accuracy and saving the operator the trouble of cleaning the part. The air jet also provides self-cleaning action for the gauge plug itself. However, the mechanical plug-type gauges become cloggy with cutting oil or coolant and may require occasional disassembly for cleaning.

The contacts and the internal workings of mechanical plug gauges are subject to wear. There is nothing to wear on an air plug except the plug itself, and that has such a large surface area that wear occurs very slowly. Air gauges consequently require less frequent mastering and, in abrasive applications, less frequent repair or replacement.

Mahr www.mahruk.com